The painting of Donald Bradman that hangs in the meeting room of Aurora Funds pays homage to the mantra of the modern hedge fund.

The painting of Donald Bradman that hangs in the meeting room of Aurora Funds pays homage to the mantra of the modern hedge fund.

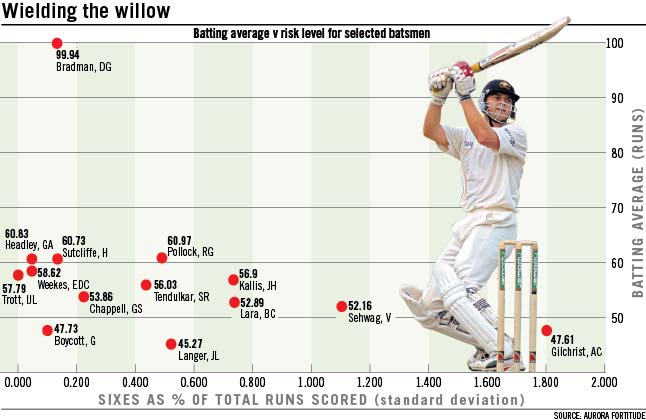

Every Australian knows – and was once even expected to know as a right of citizenship – that Sir Donald has the highest batting average of any test cricketer at 99.94. But not many are aware of how few occasions Sir Donald cleared the boundary ropes to achieve his 6996 test runs.

Only six times in his 20-year test career did he hit a six, which makes The Don unmatched in consistently making runs without aggressively wielding the willow, and risking his wicket. On the risk return scatter-plot of test cricketers, Sir Donald is an outrageous outlier.

In the Twenty20 era of the game, such doggedness in run-making might not get backsides on seats, but in the hedge fund arena it’s the Bradman-esque managers who are getting funds through the door.

“Everyone has learned that if you are getting spectacular returns it’s coming with spectacular risk and you just never know when it’s going to show up,” says John Corr of Aurora Fortitude.

“The hedge funds that have survived and have been rewarded are the ones that have provided more consistent returns.”

The changing mindset of investors towards hedge funds is best illustrated in the fortunes of two of the world’s most heralded funds – John Paulson’s Advantage Funds and Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater Associates.

Paulson is known for a spectacularly profitable bet against US sub-prime. But a horrible run since has seen his assets plunge from $38 billion to below $20 billion as his positions on the banks, goldminers, and the occasional fraudulent stock, went against him. Paulson has since given back about half of his sub-prime winnings.

Bridgewater, by comparison, has ticked along at a steadier pace, amassing a staggering $120 billion of funds under management (more than four times the entire Australian hedge fund industry).

More pension funds globally are appreciating what Albert Einstein described as “the most powerful force in the world” – compound interest.

And to harness its full power, managers need to deliver stable returns. Hedge funds and other alternative managers that can smooth out the swings inherent in markets are in higher demand than ever.

The evolving attitude towards risk and returns in the hedge fund community is manifesting itself in the broader debate among local superannuation funds about their approach.

On Wednesday evening, the Alternative Investment Managers Association hosted a panel of experts in Sydney to discuss what asset allocators can learn from hedge funds and vice versa.

An overriding theme was the need for funds to adopt the hedge funds’ obsession with managing risk above a dogmatic adherence to a pre-programmed mix of assets.

Local superannuation funds have unfortunately been more Paulson than Dalio in the past five years and are still struggling to claw back large investment losses as a result of a large weighting towards equities.

This has prompted soul searching in the industry as to whether the approach to managing pensions needs a complete overhaul.

But the crux of where asset allocation has gone wrong is not whether the fund was delivered a bad outcome. It is how it has performed relative to its “strategic asset allocation”, said one panellist.

There appeared to be almost universal agreement that funds needed to think of investment returns more in absolute sense rather against performance benchmarks. Presentations on the concept such as “risk parity”, which stresses the budgeting of risk rather than capital, are common in investment conferences attended by local superannuation funds and asset allocations.

Hedge funds such as Bridgewater have demonstrated the effectiveness of a “risk parity” approach through their strong performance during the financial crisis. Panelists also spoke of the flexibility of hedge funds to unlock value with the massive weighting to cheap credit in 2009 cited as an example of the advantages of hedge funds over traditional managers.

But there are drawbacks in placing too much faith in hedge funds, particularly when it comes to fees and the misalignment of incentives between the hedge fund manager and its clients, particularly in more benign market conditions.

The reality is the divide between alternative asset managers and traditional managed funds. Hedge funds are becoming more institutionalised and mainstream, to attract and retain capital, while managed funds have to expand their offerings and skill sets to retain it.

PUBLISHED: 20 Sep 2012 18.00.00

Written by Jonathan Shapiro